INTERNATIONAL: Elon Musk's Neuralink recently obtained approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to commence human clinical trials, an achievement that a former FDA official described as "really a big deal."

While I do not dispute the significance of this milestone, I remain sceptical about the notion that this technology will "change everything." Not every groundbreaking technological advancement has far-reaching social and economic implications.

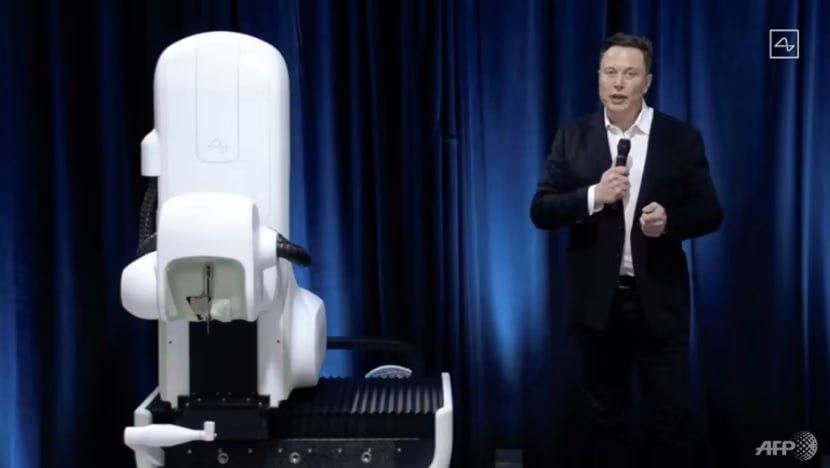

Neuralink's device involves a surgical procedure where a robot implants a device into the brain. This device can decode certain brain activity and establish connections between brain signals and computers or other machines. For instance, individuals paralyzed from the neck down could utilize the interface to interact with their physical environment, write, and communicate.

Undoubtedly, this would be a breakthrough for people with paralysis or traumatic brain injuries. However, I am uncertain about its appeal to others. For the sake of argument, assuming this technology works as advertised (given the numerous companies operating in this domain), who exactly would be interested in using it?

One concern is that brain-machine connections might be costly, limiting their accessibility to the wealthy. This could potentially create a new class of "super-thinkers" who wield their superior intellect as a source of power over others.

I find this scenario highly unlikely. Even if I were offered $100 million for a permanent brain-computer connection, I would decline due to fears of side effects and possible neurological damage. Additionally, I would insist on having control over the interaction, ensuring that the computer serves as a tool for me rather than the other way around.

Furthermore, there are alternative means of enhancing intelligence with computers, particularly through recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI). While it is true that computers can process information faster than we can speak or type, I don't feel an urgent need to keep up with that pace. I would prefer to focus on improving my typing skills on my phone, striving to match the speed of a teenager.

Another vision associated with direct brain-computer interfaces suggests that computers could rapidly inject knowledge into our brains while we sleep. The idea of waking up fluent in Chinese sounds incredible, but it also raises concerns about scenarios where computers can manipulate or control our thoughts.

However, I consider this scenario remote. Unlike using our brains to manipulate objects, the concept of computers controlling our thoughts seems more like science fiction. Present-day technologies can read brain signals, but they do not exert control over them.

Another potential application of this technology involves "renting out" the cognitive abilities of human brains, similar to how companies currently rent out space in the cloud. Certain tasks, such as identifying objectionable speech or images, are challenging for software programs. In this scenario, the connected brains predominantly belong to low-wage workers, reminiscent of how social media companies and OpenAI have utilized low-wage labourers in Kenya to assess the content quality or make content-related decisions.

While such investments may raise the wages of these individuals, critics may argue that it could create a new and insidious form of class distinction: those who rely on brain-computer interfaces to earn a living versus those who do not.

Could there be situations where higher-wage workers would desire to connect to these machines? Would it be beneficial for spies or corporate negotiators to receive real-time computer intelligence while making critical decisions? Could brain-computer interfaces find use in professional sports, guiding a baseball player on when to swing and when to hold back?

The more I contemplate these possibilities, the more sceptical I become about the widespread use of brain-computer interfaces for non-disabled individuals. Artificial intelligence has made remarkable progress, and it does not require invasive procedures on our bodies, let alone our brains. We can always rely on earplugs or envision a future version of Google Glass.

The primary advantage of direct brain-computer interfaces appears to be speed, which is crucial only in specific circumstances, many of them competitive or zero-sum in nature, such as sports and games.

Of course, companies like Neuralink may prove me wrong. However, for now, my confidence lies with artificial intelligence and large language models, which sit comfortably a few inches away from me as I write this.

What do you think? Will BCIs become a common part of our lives? Or will they remain a niche technology?